Who will care to tweet about Libya now that the bombing is over?

The Starbuckian brigades look to Egypt convinced their power to Tweet and change history undiminished.

Our bet? No one.

The Imperial City And The World

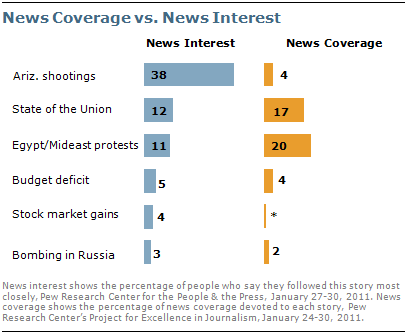

So far, the extraordinary anti-government protests in Egypt have drawn much more attention from the news media than from the American public.

Only about one-in-ten (11%) cite news about protests in Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries as the story they followed most closely last week. By contrast, more than three times that number (38%) followed news about the aftermath of the Jan. 8 Arizona shooting rampage most closely last week, according to the latest News Interest Index survey conducted Jan. 27-30 among 1,007 adults.

Remember when Baker sold the Gulf War as being about ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’? The new Pew Survey indicates the Administration may have little recourse, soon.

The days of British military power appear to be ending” Max Boot lamented in the Wall Street Journal. Another columnist at The Economist weighed in that Great Britain is at best managing its “relative decline

That was likely not the reception that U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron’s coalition government was hoping their new National Security Strategy would receive from such traditionally conservative outlets when it was released Oct. 18. Coupled with the Security and Comprehensive Spending Review released days later, the critics worried that these documents were merely written justifications of the end of Britain’s military footprint in the world.

Yet it is odd that a conservative government was lashed by fellow travelers for the very reason of making strategic decisions based on realism. That is, the security strategy, titled “A Strong Britain in an Age of Uncertainty,” can be read as a realistic blueprint for tough times, reflecting the priorities of a new government — chastened by what it says is the overreaching of its predecessors, but which nonetheless continues to endorse a global role for the U.K.

Even more, the documents may have some lessons for leaders on the other side of the Trans-Atlantic “special relationship.” As Cameron noted, “We have inherited a defense and security structure that is woefully unsuitable for the world we live in today. We are determined to learn from those mistakes, and make the changes needed.” Cameron’s statement was more than just putting a brave face on grim news. It was an illustration of what a government sometimes has to do when facing tough circumstances. And, given current circumstances and trends for the U.S., the British document may well provide some inkling for how an American president and defense secretary, Democratic or Republican, will likely respond in 2013 and beyond as the U.S. wrestles with its own “age of austerity” (emphasis added).

We first met Adam Garfinkle 30 years ago or so when he was starting out at FPRI. We’re under no illusions about his ideological prisms. His re-printed piece in “The American Interest”, ‘An Innocent Abroad: The Obama Foreign Policy’ easily could come from Hudson or the usual suspects. Yet he correctly observes:

Indeed, the fuzzy indeterminacy that characterizes the Obama foreign policy holds true even at the highest echelon of strategy. The United States is the world’s pre-eminent if not hegemonic power. Since World War II it has set the normative standards and both formed and guarded the security and economic structures of the world. In that capacity it has provided for a relatively secure and prosperous global commons, a mission nicely convergent with the maturing American self-image as an exceptionalist nation. To do this, however, the United States has had to maintain a global military presence as a token of its commitment to the mission and as a means of reassurance to those far and wide with a stake in it. This has required a global network of alliances and bases, the cost of which is not small and the maintenance of which, in both diplomatic and other terms, is a full-time job.*